005*bis. Anna Ivanovna Vel'jaševa-Volynceva / Анна Ивановна Вельяшева-Волынцева

Anna Ivanovna Vel'iaševa-Volynceva, born in 1755, was subject of an earlier post. In 1764, at the age of nine, she published a translation of Madame de Gomez's Histoires du comte d'Oxford, de milady d'Herby (1737) and did so under her own name. She went on to publish translations of Gueulette's Les Mille et Une Heures (in 1766-1767) and Frederick II's Brandenburg History (1770). Our narrative then stopped, when Anna Ivanovna's translations stopped appearing in print, presumably after her marriage to a certain Olsuf'ev.

We have since uncovered details involving identity of her spouse. Anna Ivanovna married Michail Matveevič Olsuf'ev (1733-1801), 22 years her senior, and member of an illustrious family.[1] Olsuf'ev's father had been Head Chamberlain (ober-gofmejster) at the court of Catherine I, wife and successor to Peter I, while his uncle had held the same position in Peter's own court. As a result of Anna Ivanovna's matrimonial bond with Michail Olsuf'ev, she and her family also found themselves connected to other prestigious clans, including the Senjavins and the Saltykovs.

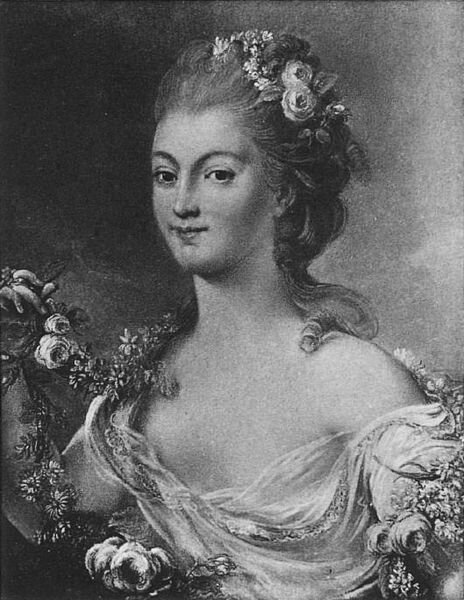

Of particular note within the extended Olsuf'ev family itself were the figures represented in the portraits gathered here: Michail Matveevič's elder brother Pavel Matveevič (1728-1786), who distinguished himself in the Russo-Turkish War (1768-1774); his sister Praskov'ja Matveevna (1730-1813), who married the wealthy and cultured Aleksandr Grigor'ievič Demidov (1737-1803), scion of an important industrialist family who had spent more than a decade abroad (with two brothers) perfecting his education; and Michail Matveevič's cousin, the prominent Adam Vasil'evič Olsuf'ev (1721-1784), who enjoyed important positions in several successive reigns and eventually became a trusted secretary to Catherine II.

It's easy to imagine that the prospect of a firm link to the Olsuf'evs would have pleased Anna Ivanovna's family. Indeed, the standard elite practice of marrying younger women off to older men had a peculiar feature that bears remarking: Anna Ivanovna's husband was older than her own father, the renowned professor of military engineering and textbook author described in our earlier post. Thus, as Anna Ivanovna was wedded to an older man, her father, her brother, and other family members whose careers or fortunes stood to profit by this connection were simultaneously soldering their own ties to a man who was senior to them in both age and position.

But what did Anna Ivanovna offer to her husband? We don't know if she was particularly rich or beautiful, but she did stand out for her marked intellectual proclivities and, as we have seen, also belonged to an unusually educated and intellectual family. These characteristics would seem to have added to her appeal: after all, Michail Matveevič selected her rather than another bride. More generally, cultural interests were broadly diffused in the Olsuf'ev clan, suggested both by Praskov'ja Matveeva's marriage to a man renowned for his education and by the example of cousin Adam Olsuf’ev, who had studied abroad (Upsaala), sent his son to the University of Leipzig (where he was a classmate of Aleksandr Radishchev's), traveled in Europe and worked in Copenhagen in a diplomatic capacity. Proficient in many languages, a connoisseur of music and theater, a translator, poet, and associate of the writer Aleksandr Sumarokov, Adam Olsuf’ev made a great impression on contemporaries for his learning.[2] Certainly, his literary interests overlapped with those of the Vel'iašev-Volyncevs.

As stated in our earlier post, we know very little about how Anna Ivanovna's life evolved after marriage or even when she died. Her husband began his career in military service and later assumed a series of civil posts in the field of jurisprudence. He and Anna Ivanovna had two sons, Fedor and Matvej, both of whom appear to have followed their father in serving successfully to reach the exalted rank of Actual State Councillor. Did their mother live long enough to enjoy their success or to instill in them her own cultural interests? In theory, the Olsuf’ev family seems like it may have been as capable of supporting female literary activity as the Vel'iašev-Volyncev family had been. Did Anna Ivanovna continue to translate as a wife and mother? And when Michail Olsuf'ev was buried at the Želtikov monastery in the gubernija of Tver in 1801, was Anna Ivanovna there to mourn him?[3] As usual for women writers in this period, there are more questions than answers. What we have found, however, is evidence that Anna Ivanova Vel'iaševa-Volynceva's literary inclinations did not diminish her marriage prospects and may even have enhanced them.

Notes:

[1] Rossijskaja rodoslovnaja kniga, čast' 4 (SPb. Tip. Karla Vingebera, 1847), 439.

[2] On A. V. Olsuf'ev, see V. P. Stepanov, Slovar' russkich pisatelej XVIII veka, vyp. 3 (SPb.: Nauka, 1999), 383-87; B. Sulpasso, "Pis'ma A. V. Olsuf'eva k Ja. Ja. Štelinu iz Kopengagena", XVIII vek, sbornik 26 (2011) 353-67.

[3] Russkij provincial'nyj nekropol', t. 1 (M.: I. N. Kušnerev, 1914), 23. Michail Matveevič's surname appears here under the alternative spelling "Alsuf'ev.'

Illustrations:

1. This portrait of Praskov'ja Matveevna Demidova (née Olsuf'eva) by Pierre-Antoine Baudoin and dating to the 1760s is housed at the New York Public Library. (Courtesy of Russian Wikipedia)

2. Portrait of Pavel Matveevic Olsuf'ev (undated and by an unknown painter) is housed at the Nižegorod State Museum of Art in Nižnyj Novgorod. (Courtesy of Russian Wikipedia)

3. Portrait of Adam Vasilevic Olsuf'ev (1773) by Carl Ludwig Johann Christineck. (Courtesy of Russian Wikipedia)

4. The Želtikov Monastery in the 1890s. (Courtesy of Russian Wikipedia)